To See Each Other

Episode 6: Seeing Each Other - Indiana

Episode Summary

George goes back home to Indiana, where members of Hoosier Action are refusing to give up on fellow Hoosiers. George recalls growing up with Kate Hess Pace, founder of Hoosier Action. Members of Hoosier Action like Tyla Barrick Pond, Scott County physician Dr. William Cooke, and Tracy Skaggs detail environmental hazards and the devastations of Indiana’s opioid epidemic. Together, they have made space for shame to turn into vulnerability and creative resilience.

All these Hoosiers–George included–testify to how when we see when we see each other, we strengthen our communities together. And we win.

Guest Bios

Kate Hess Pace

Kate has worked in organizing and advocacy for the past 20 years. Prior to starting Hoosier Action, she worked as a community organizer for ISAIAH in the Twin Cities for 8 years working to develop the leadership of people who have been left out of public decision making. She led the campaign to win the Homeowners Bill of Rights, securing some of the strongest foreclosure protections in the country, she was an integral part of the successful efforts to defeat voting ID on the ballot in Minnesota, and she worked with Director Richard Cordray of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to put forward some of the first federal rules on predatory lending. Kate is a national trainer, leading trainings and workshops for community leaders across the country for several years. She is a sixth generation Hoosier and deep believer in the potential of the state and its people.

Learn more: The Forge

Dr. William Cooke

Dr. Cooke is a family medicine doctor in Austin, Indiana. He is the medical director and founder of Foundations Family Medicine, P.C. He runs the hospitalist program at Scott Memorial Hospital in nearby Scottsburg, manages three school-based clinics, and teaches at Marian University College of Osteopathic Medicine and Indiana University School of Medicine. In 2018, the American Academy of Family Physician named him Family Physician of the Year. He is finishing a book called Canary in the Coal Mine. Dr. Cooke and his wife, Melissa, have six children.

Tyla Barrick-Pond

Tyla works as a home health care aide and leads Hoosier Action’s environmental justice campaign in Franklin, Indiana. She’s brought others along with her and led a community campaign to force the powers that be to clean up Franklin. She chaired a community rally with over 100 people and was at the center of the testimony from impacted residents that finally moved the EPA to create a clean-up plan for the area. Tyla and her husband have four amazing kids.

Learn more: Hoosier Action

Tracy Skaggs

Tracy is a mother, grandmother, and a leader at Hoosier Action. Five years ago, she began to recover from a heroin addiction. Since then, she’s gone back to school, earned her bachelor’s degree, found her church, and has continued to work with communities of recovering addicts.

Learn more: News and Tribune

Transcript

George Goehl:

This is To See Each Other, where we explore how people are reshaping small town America. And why writing it off as Trump country hurts us all. I’m George Goehl, and today, I invite you home with me to Southern Indiana. Indiana has my heart. It’s also where the most pressing issues of our time come together, and maybe our solutions too.

I live in Chicago now with my wife and daughter. I’ve been here a long time. Chicago is where I came into my own as an organizer, and where I found some of my greatest teachers, and lessons. But I love Indiana, especially southern Indiana. It’s the place I love most in this world. It’s deep in my bones. Southern Indiana is rolling hills, and hidden hollers. It’s driving through tiny sea through towns windows open with the summer heat pushing through the cab of a truck.

Freetown, Story, Stone Head, Gnaw Bone, and Bean Blossom. Few things are better. At least to me. I love Indiana basketball, and the way our love for it is everywhere. From the front page of the paper to the conversation at the barbershop into the hoops bolted on the fronts of barns all across the state. I love paddling on Crooked Creek, round barns, and covered bridges in limestone, Indiana limestone.

That limestone was pulled out of the ground to build iconic American structures, like the Empire State Building, and the Washington Monument. Hoosiers are proud of that. But just as proud of the holes left behind, those quarries they filled with water, and those swimming holes became our monuments.

The writer Scott Russell Sanders summed up what I love best, the smell of hot tar bubbling in the joints of the road. Creosote in the telephone poles, windblown dust from the fields, the mustiness of new mown hay, the green pungency of Queen Anne’s lace, and chicory, and black-eyed Susans. These senses, even the thought of them still make me melt. I may be in love with Indiana, but it’s not without its share of flaws, maybe more than its fair share. Indiana is in political terms, a red state.

It was never part of the blue firewall in the Midwest. Every other Great Lakes State was. LBJ was the last Democratic presidential candidate to win Indiana, with the singular exception of Barack Obama in 2008. It is a state of contradictions. It gave us Eugene Debs, the socialist labor leader who ran for president four times. It’s also the state that gave us Mike Pence, who grew up 20 miles down the road from where I lived as a kid, and where my dad lives to this day. He graduated from the same school where my dad taught shop in the 1970s.

Indiana, a manufacturing hub was home to epic, and impassion union struggles with steel and automotive workers risking lives, and livelihood for fair wages, and the right to organize. Like North Carolina, it was also a stronghold of the Ku Klux Klan. In the 1920s, Indiana had the highest number of Klan members of any state in the country. Nearly one out of three white men in Indiana were members of the KKK. One out of three. Membership swelled in reaction to immigration of workers from Eastern and Southern Europe. Sound familiar?

Like we saw in Michigan, North Carolina, Iowa, New Jersey, Indiana has been hit with a potent combination of job loss, corporate pollution, and racial resentment to leave us with divided communities, decimated small towns, and a deep sense of loss. Those small towns that I love, they’re dying now. I grieve for them like I would anybody that I love, and I have.

Last summer, three of my friends from back home died deaths of despair. One overdosed, one struggled with alcoholism to the end, and another had been homeless for much of his adult life. They say he fell asleep and didn’t wake up. So often, we give up on people like my friends, we give up on places like Indiana, we write them off, especially when they no longer feel politically useful.

Especially, when it feels like we no longer have anything in common. Why would progressive folks reach backward to these red states when we could solidify our position with people who already think like us? But giving up on red states, means giving up on the people there. All of them. White rural people, yes, but also black, immigrant, native, Asian, Latinx, and queer people.

I can’t do that. We can do that. Before leaving Indiana to move to Chicago, I used to sit in what was called the Indiana Room of the local public library. I’d call through maps, census, data, and more, mapping out the contours of building a people power organization in the state. I never ended up doing that in Indiana, but an incredible organizer did.

When Kate Hess Pace, a Hoosier who had moved to Minneapolis to organize called me about coming back home to start an organizing project in Southern Indiana, I was elated, and maybe a tad envious. But Kate was so clear from go on the need to organize in small towns, and rural areas, places progressives had written off long ago, or maybe never even wrote in.

Kate saw the opportunity to bring people together, to challenge the architects of so much pain in Indiana, those leaders, and institutions who seek to divide, and shame everyday people for their own benefit, and at the expense of everyone else.

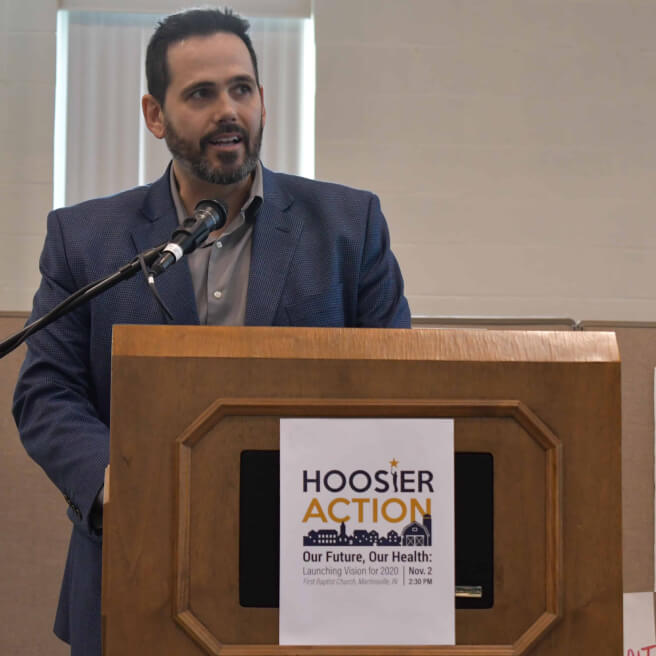

And she came with this vision of raising the ceiling of possibility for all Hoosiers. It’s with that she started Hoosier Action, an affiliate of People’s Action that organizes across party lines, and for the people.

Most people don’t think about Indiana outside of Indiana. Can you give people a sense of what folks are up against?

Kate Hess Pace:

So, the economies that built the state have been almost fully demolished. So, family farming isn’t really a viable option. We have some counties that every stretch of farmland has been consolidated into corporate farms. And then, the majority of decent manufacturing jobs have left. There’s no small-town economy really. Many of our small towns, it’s a dollar store, gas stations.

There’s just no place to build a decent living wage job to have one. We’ve had a long-standing problem with meth, then the opioid crisis hit this region really hard for a whole number of reasons. One, the economic devastation, and two, just being a thoroughfare to other cities with stops along the way.

I don’t think anyone would describe Indiana as progressive, but we had Democratic governors. My whole life, we were a ticket splitting state. Indiana went for Obama in 2008. And then, I really think Indiana was the canary in the coal mine for the backlash to Obama, and the subsequent Tea Party movement, and then the election of Trump. So, in 2010, there was an enormous sweep, and a trifecta emerged in our state government house, senate, and governor.

Then right to work past in 2011, demolishing our labor unions. And then, that has led to a whole bunch of ripple effects that have stripped people of power, and then just extracted a lot of wealth out of our state. There is a weight, like a crushing weight of this feeling that the potential for opportunity, and dreams, and human life has been crushed.

People that can leave, leave. There’s not a ton of pride in a lot of places. And being from here, even though you and I know what a beautiful place it is. All this being said, there are people holding it down with duct tape and string, like helping their community. There’s leadership gold in all these places.There is amazing people that do everything they can to help each other out, and to solve problems that they shouldn’t have to solve. But it really is so much harder than it has to be.

George Goehl:

When I was coming to attend the meeting you held in Martinsville, you said this meeting might not, and likely wouldn’t be legible to progressive activists, or organizers. Can you say more about what you meant by that, and why that is?

Kate Hess Pace:

So, there is a lot of terminology, language, and cultural performity wrapped up in progressive spaces. That doesn’t really translate to the leader that came in because she worked at rallies, and her boss wouldn’t give her any breaks, and she miscarried. And that’s why she’s in the room. She’s not in the room because we talked to her about using the words of white supremacy, capitalism, and patriarchy.

We could move her, and we are moving on getting people more oriented to gender, and being inclusive. But that’s not why she’s in the room. So, if we start from that place, which is this signaling to people that are like us, it actually creates really exclusive spaces. Instead of starting with values, giving people the experience of being seen, I find many progressive spaces are pretty elite in their terminology.

And they’re for people that have high levels of education, which is not the project we’re doing, and not the projects that I want to build, which is really about fighting around the idea that there’s no expendable humans in our state. That we are destroying everything that’s sacred about the place that I’m from, and we’re trying to build an army to fight back against that.

So, I think that progressives have to decide if they truly believe that we’re fighting for the worth, and dignity of everybody. And if that’s true, then we need a multifaceted plan. And that plan cannot write off whole swaths of our country, who have been also devastated by the inhumane cruel systems that we have in place. So, that’s one thing too, is our places, they’re not one thing.

There are all different kinds of people trying to make a life here. And I just am a deep believer that good, disciplined organizing brings solid gold out of the shadows into leadership. It’s not sexy, romantic Instagrammable work. Its organizers knocking their 45th door of the day, and finding somebody who’s been waiting for a different story, and an invitation to do something different that fights for their dignity.

So, I guess I would ask in the same way that I ask the organizers, and the leaders is like, “Can we put, and bake into our movement a little bit more curiosity about who people are, and what they need, and more of a real invitation?” So that our movement, that lots of people can see themselves inside of it.

George Goehl:

I love the notion, that solid gold, in terms of people, and future leaders can be found anywhere, and everywhere if we do the hard work of organizing. The first organizing axiom I was taught was start where people are at. And that’s exactly what Hoosier Action is doing. Hoosier Action is building a big tent. Every Hoosier, regardless of politics is welcome to build with the organization to strengthen their communities, and create meaning.

The organization works on everything, from protecting health care, and preventing evictions, to get out the vote campaigns, to fighting the opioid crisis, and supporting environmental cleanup. Hoosier Action builds the power of everyday Hoosiers who have been left out, and left behind.

And that’s a lot of people, because at the heart of it all, Hoosier Action creates space for people to share, and bear witness so they can release their shame together. The result? Communities build the bonds needed to understand, and challenge the structures, and the narratives that hold us back. So, I’m inviting you now to listen to the story of Tyla Barrick-Pond.

Tyla was deeply ill when she learned through Hoosiers Action that her home in Franklin, Indiana was less than a mile from where the multibillion-dollar company, Amphenol, had leaked toxins into the soil. Among the toxins were TCEs, and PCEs. Known carcinogens that created a cancer cluster in the region, among many other illnesses. Tyla, 27 years old, barely survived.

Her experience can provide a deeper understanding of how corporate overreach, and lax environmental regulation by the government by the very people who’ve been elected to protect you can devastate your whole world. And yet Tyla’s story was and is one of hope. Her testimony was at the center of a successful Hoosier Action campaign to push the EPA to create a plan to clean up Franklin. She’s here to share her story.

Tyla Barrick-Pond:

I was sick for a while. I went to immediate care. I went to Johnson Memorial, and they all said, “You have a virus or I ended up having strep at some point.” So, they gave me medications for that. I went to my primary, she said, “Oh, strep didn’t go away, here some more medicine.” And I still didn’t feel right. I was really tired. I had a cough.

And just, I knew something was wrong. So, I went to the hospital, and I already had sepsis. I was in heart failure, and lung failure. And I ended up being in a medically-induced coma for nine days. And they say if I hadn’t come in, I would have died. But I know I was lucky. And I got there just in time. I got the help that I needed.

When I came to, they sent samples to CDC, as much as they could for all kinds of things, and everything came back negative. They didn’t understand why I was so sick at that point. I want to say in 2016, Erin Brockovich had gotten involved, and it became known that there was contamination in the site. So, then they started offering testing to the houses that live next to it.

And that’s when I realized that it had spread to the houses that were on the same intersecting street. So, at this point, they’re testing those homes, and they were putting devices in our home to ventilate the toxins from their crawl spaces. But they never offered testing outside of certain parameters. And unfortunately, they said that my house is outside that perimeter, but it got really bad.

Webb Elementary and Needham Elementary started testing, because they’re right in the vicinity. And Webb tested positive for TCE and PCE. And they canceled school, I think, for one or two days. They sent out paperwork on what classrooms were contaminated in the area of the buildings, and what were not, but it was not reassuring enough to me.

So, I pulled my daughter out of Webb, and I homeschooled her. I was not comfortable. I knew that I couldn’t change the home environment. But I assumed, logically speaking that the school’s exposure was higher than my home at this point. They had a system installed the following summer that would ventilate any toxins in the school appropriately.

So, we put her back once they installed the system in the school. We moved in September last year, and it was a huge decision for us to make. It was not one that we could do financially. So, I ended up having to go back to work. But our kids had stayed sick. I have a special-needs four-year-old that has cerebral palsy, and a feeding tube, and she aspirates fluids.

So, she’s sick on her own a lot. But then, my other two would be sick as well. I was going to the ER at least once a month. The things that would happen to me just weren’t normal. They would get every weird rash, and an oddball sickness all the time. And since we moved in September, my kids haven’t been sick. I feel like you shouldn’t have to make that choice between being financially comfortable, and not being financially comfortable to be healthier.

But unfortunately, that’s what we had to do. We had to make that decision. And because I had to find nursing for my four-year-old, because she has tube feedings, and that’s something I can’t financially, or safely do is put her in daycare because she’s medically fragile. So, we had to make that choice. It shouldn’t be that way at all to have to do that.

I would look at my kids while they were sick, and I would feel terrible because I knew that something was wrong. And it wasn’t until I learned as much as I did about the contamination, and then the effects of TCE and PCE on your body, that I knew something was wrong with my kids. When you talk about it in Franklin, it’s like taboo, no one really wants to hear about it.

They want to act like it’s not an issue. But when it affects your life on a daily basis, you get angry because you know it’s there. You can’t look at an apple, and not call it an apple. Everyone in the house was sick. I almost died. We’re near the contamination site. I wasn’t like this before we moved. My kids weren’t like this before I moved, and we’re just stuck. And it’s disheartening when no one will listen.

The audacity of knowing what those chemicals can do to people, let alone, let it distribute throughout a community. Because the houses, they’re right on the same road. There’re families, there’re waterways, there’re lives, and they pretty much just said, “The dollar is more important.”

George Goehl:

I’m so grateful to Tyla for sharing her story. And most of all, for continuing to fight. To know that the home you live in is poison, and its poisoning you, and your child, and to have to go back there to live anyways, that’s a tragedy. But Tyla did more than just survive. She has with her bravery and honesty, led a community campaign to force authorities to continue to clean up Franklin.

She chaired a community rally with over 100 people, and continues to lead even if she cares for her own family. What an example of holding it together with duct tape, and still working to make the world a better place for others against all odds. Tyla’s experience represents to me what our next guest, Dr. William Cooke calls a social sin. A failure to make sure that we can all live healthy, dignified lives.

I believe this idea shows up in lots of places, like when some corporations, whether they’re hog operations in Iowa, or negligent companies in Indiana, can determine who gets to drink clean water, and breathe clean air, and who doesn’t. It’s the idea that somehow only some people living a certain life deserve health. It goes against everything Dr. Cooke believes.

Dr. Cooke is a Hoosier born and bred. He grew up in New Albany, deep in southern Indiana. He knows well the needs of his community in Scott County, where he established his practice right after residency, not 40 minutes from where he grew up. Before he started his practice in 2004, there had been no doctor in the area since 1978. I’ve thought a lot about what signifies that a town has died.

Is it when the movie theater closes? The only school, or the last church? But consider that there might be no doctor anywhere in your community for nearly 30 years. Scott County is also where in 2015, there was the largest HIV outbreak of its kind in the US. It was a confluence of events that was the result of the economic decline of the region, and the burgeoning opioid crisis, all made even worse by then-governor Mike Pence’s punitive needle exchange laws. Dr. Cooke’s care has brought the new infection rate down to zero. He is a reminder that one person choosing not to give up on a place that’s so many have given up on can have major impact.

Here’s Dr. Cooke to tell us about it. Can you take us back to 2015, and explain to somebody that’s never heard about the crisis in Scott County, what happened?

Dr. William Cooke:

In our particular area, the opioid crisis was overwhelming and devastating. Most people in the community were at risk for developing opioid use disorder just because of the toxic stress that they were constantly living in, and growing up in. So, the community started experiencing more injection drug use when formulation started changing with some of the medication that people were using.

They would typically, crush it up and snort it. But because the formulation changed to try to prevent that, they figured out a way to melt it down, and inject instead. So, it was an unintended consequence of an effort to decrease drug use led to actually increased drug use in an intravenous way. And because clean syringes were illegal in Indiana, people couldn’t access clean syringes.

So, they were reusing them over, and over again, and sharing them. They started spreading different diseases like hepatitis C, some people contracted endocarditis, which is a serious life-threatening infection on the heart valve. We started seeing these things. We knew something devastating was happening.

As far back as 2011, advocates were saying we need a syringe service program to be able to get clean syringes, and start working with people that do feel disconnected, and isolated, and marginalized in the community that may feel unsafe asking for help. But none of that happened. And so, in 2015, Austin, this small town of 4,300 people ended up having the worst drug-related HIV outbreak in US history.

The first couple of cases were diagnosed at Scott Memorial Hospital in December of 2014. And another eight people were identified in early January, and these numbers continued to increase. Finally, in March, we met with the Indiana State Department of Health, and talked through what was going on, and what we need to do because I was the only medical access in Austin.

I offered to open my office up to anyone that was at risk, or had contracted HIV as a place that they could come access health care, and behavioral health, and addiction services, and HIV care as well. So, the state helped me connect with different resources. The CDC came in, HRSA came in, Governor Pence signed an emergency order, giving us access to state resources, including an exemption from state law to allow us to run a syringe service program.

We brought in some infectious disease doctors to help me learn how to provide HIV care. We connected with a couple behavioral health centers to be able to provide mental health, and addiction services. And we became this hub of care, and not everybody liked that. The first weekend before we opened officially, the new HIV access point in my office, we had death threats.

We had some people call saying that they heard that we were going to have our building burned down. There was a lot of people calling, telling us that we were going to rot in hell. Basically, how dare we take care of those people. We’re going to get what’s coming to us. Some of my patients said that they’re going to leave the practice. Go to another physician, people picking up their medical records.

We had a lot of backlash because I had decided that every single person in the community was a person, regardless of what label he placed on them. And that we were going to be available to anyone or no one. And so, come Monday morning, I drove in nervous, didn’t know what to expect, remembering what Ryan White grew up with here in Indiana, half expecting picketers out there with signs, and who knows what.

Didn’t even know if my building would still be standing because of people calling saying they were going to burn it down. And got there, and there were no picketers, the building was still there. Locked in, started providing services to people. CDC and public health experts, they were really, really concerned. Nobody had ever seen anything like what we were dealing with.

This was the worst drug-related HIV outbreak in US history, the first significant HIV outbreak in a rural setting. Nobody knew how to respond to this. My principles were basically to one, make sure that everything we did was patient centered, that we would surround each patient with all the care that they needed individually.

That everything that we did would have some tie to the community, and not be relying on outside sources. And then, the third, for it to be sustainable that we didn’t want to rely on what the governor funded, or what grants did that we wanted to be able to keep whatever we started going forward.

And fourth, to allow every single person to feel safe, to not feel threatened, to know that they could come in, and be vulnerable with us, and let us know where they were, and how things were going, and that it was okay that they weren’t okay right now, that we would help them no matter what life looked like for them.

George Goehl:

As a doctor, if you could write a meta-level prescription to heal poor rural areas in America, what do you think are some of the key things we need to be thinking about?

Dr. William Cooke:

Well, growing up, I grew up in an Appalachian fire and brimstone church. And a lot of that was based on making sure that you are right before God, and that other people, they also needed to get their lives right. And if they only live that righteous lifestyle, they wouldn’t be experiencing the consequences, those harmful consequences in their lives. So, that’s what I grew up with.

When I went to Austin, I started seeing that these were people who were not being harmed because of personal choices that they made, like I had believed growing up. But these were people that were being harmed by what became known to me as social sense. I started believing that society can sin against people by restricting how much access they have to life.

We have in place, modern science, modern medicine, modern social advances that should allow people a certain level quality of life, life expectancy. Yet, here’s a community whose life expectancy was reduced, the disease burden was increased, their access to a future, and opportunity was suppressed solely based on where they lived, and how much access the rest of us were willing to invest in them.

I believe that allowing people to have access to health care, regardless of whether or not we think they should, what we think about somebody should have no relevance on whether or not they can access health, and opportunity in America. We need to have local health care providers that are accessible to people, where people can come in, and feel safe accessing health.

And that they’re not going to get fired if they miss so many appointments, or they’re not going to get seen because they don’t have health insurance. Every single person needs a doctor, and to invest in that isn’t Republican, or Democrat, or liberal, or whatever. It’s just compassionate. It’s human.

George Goehl:

When I sit back for a minute, and reflect on all the places we’ve been on the show, thinking about homes washing away in New Jersey, or the thirst for clean water in Iowa, or making new friendships in North Carolina, this is what I think connects them all. It’s just about compassion, about being human. About how when we let ourselves be seen, and when we see each other, that’s what’s undeniable.

I remember a Hoosier Action meeting I attended last year, where person after person got up, and share their story, their story of what they were up against. And what I really heard people saying, and asking was, does it really have to be this hard. And sitting in this meeting with hundreds in a church in a very conservative county, I witness something happening that we as Hoosiers are not taught to do. Be vulnerable.

We were taught, I was taught to buck up, and never show weakness. And here, Hoosier Action is doing something quite radical, something that is countercultural, getting folks in small towns, and rural communities to be vulnerable. And in doing that, they’re releasing the shame, and recognizing that they are not alone in their issues.

One of the greatest issues that Hoosiers are facing is addiction. It’s a struggle I’m deeply familiar with. By the time I was 20, I was deep into drugs, and not good ones. I’m still sorting out for me, whether it’s body chemistry, childhood trauma, or maybe both. On the best days, I had good friends, and adventures that I am to this day glad for. On the worst days I was homeless.

I’d find myself in rooms with drugs, and guns at the same time, which is never a good thing, or sneaking into vacant properties to strip copper, or stainless to make a few bucks at the local salvage. And worst of all, I felt powerless to change any of it. I eventually got a job washing dishes at the soup kitchen, the same one I was eating at.

And soon, I realized people eating at the kitchen needed me to see them, to connect as they came through the door, to give someone a little job to do, to feel part of the team, to lend an attentive ear to someone to tell their troubles to. And all of this required me to get clean. I rented half a trailer a mile down the road. I had a bedroom, and a little living space, and shared the kitchen.

There was no running water, no toilet, and one working outlet in the entire place, and it was all that I needed. I would ride a bike to the soup kitchen, and work, and be with people. And then, I’d head back to the trailer, sequester myself, and go back to the kitchen the next day, and just do that over, and over, and over. And I’d go days without using, and then I backslide.

But eventually, things evened out. And looking back, it was Vaness, the cook at the kitchen, an Armenian man from Beirut, who, despite all my failings, saw me, and gave me a chance. And then, another person saw me, and another. And those people changed the course of my life. My story is both infinitely common, and tragically rare.

And in Indiana, there are tragic stories, but also beautiful ones. Tracy Skaggs, a leader at Hoosier Action shares how her community in Floyd County, also in Southern Indiana is surviving the opioid epidemic that still rages through much of the United States.

Tracy Skaggs:

I am a five-year recovering heroin addict, and addiction, there’s not one aspect of my life that addiction has not touched. I grew up the child of an addict. My addiction actually began at a young age. My mother introduced me to marijuana when I was four. I was snorting cocaine, and drinking at the age of 13. And then, I’m married an addict. And I’m also the mother of an addict. So, again, there’s not one aspect of my life that addiction is not touched.

George Goehl:

Do you feel people in Southern Indiana have been hit hard more lately than maybe 10, 20, 30 years ago?

Tracy Skaggs:

Absolutely. This opioid epidemic has really had a huge impact on Southern Indiana. So many people mourning the loss of their child, their mother, their father, their brother, their sister. They are angry because they cannot get their loved one help. They are in a state of desperation because they don’t know where to turn.

Tracy Skaggs:

And you hear the state say call 211, or look into SAMHSA, or just get help. Well, getting help is not that easy. And to be honest with you, even the hospitals in this area, and I’ve come up against them too, and I just did not too long ago.

George Goehl:

I believe that.

Tracy Skaggs:

I caused a stink on Facebook over… I did, a young lady who was homeless, and she’s an alcoholic, and she decided she wanted treatment. So, some of the homeless outreach volunteers here reached out to me because that’s my area of passion. And we first tried with one of the mental health institutions here, and they would not take her because her blood alcohol level was a 0.5, which is lethal.

That could lead to alcohol poisoning. So, they called an ambulance, and she was taken to Scott Memorial Hospital. And she has a twin sister, and her twin sister has a bad reputation. And so, no sooner than we had pulled off, this young lady was escorted out. She didn’t even have an assessment, a physician. They had security, and they were not going to do anything about that.

And it is very well known, even in community college curriculum that alcohol requires a medical supervised detox because it could kill you. And with her blood alcohol level being that, they just turned her away, and put her on the street. And basically, said good luck with that, and that was not okay with me. It is putting a young lady’s life at risk when their profession is to save lives.

So, I created a stink, and it’s being addressed at the hospital. And I’m happy to say that this young lady, because I’ve reached out to some other people, is now in treatment, and she’s doing amazing. But there is as much stigma in the hospital when it comes to drug addicts, or alcoholics, as there is in the rest of the world. And that’s a big problem.

We are up against our local, and state governments to overlook us, or make us feel as if we don’t have a say in the matter. There’s a lack of compassion. And personally, I feel like a lot of us are just left here to accept what people say is okay for them to do with our lives, or not do with our lives, or we’re just left here to hang. And the people here need to know that someone cares.

They need to know that there’s someone that they can relate to, that is not scared to be their voice. And to remind them that we, that our state, our local governments work for us. We do not work for them. And unless we find our voice, and stand up for ourselves, we’re going to continue to be pushed back in the corner, and made to be quiet.

George Goehl:

Push back in the corner. It sounds like, currently, some people are disposable, and some people aren’t.

Tracy Skaggs:

Absolutely. That’s exactly perfect words. There are a lot of beautiful people who have wonderful talents, who have just had life try to rip their throat out. And we fight. People see addicts as being weak. But I would challenge them to say, “Come inside my head, and walk in my shoes. And tell me if you could do it.” Because it took strength to survive my childhood. It took strength to endure the drugs. It took perseverance to get out of homelessness. It took grit to become who I am. It took fearlessness.

George Goehl:

Tracy, listening to you, I’m reminded that whether being poor, homeless, addicted, like how much resiliency, and grit, and creativity, and ingenuity it takes to get through the day.

Tracy Skaggs:

We are very resourceful. Yes, you have to be in order to survive through the day. I’ve also said too, many a times that when you find an addict who has found recovery, and is making that transformation, that would be one of the greatest employees for a company to have.

Because they’re going to be appreciative. They’re going to be grateful, and they’re going to fight for you the same way that they fought for their life. And that’s what I’m out here doing, where some people don’t have the energy to fight, I’m out here fighting for them. Because they matter, and I care.

George Goehl:

Tracy, you were an inspiration, seriously. Yeah. I’m just so glad that, feel honored to get to talk to you, and so glad you and Hoosier Action found each other. And yeah, it makes me really excited about what you’re going to pull off. I feel like you’re just getting started too.

Tracy Skaggs:

I am. I like to raise the bar.

George Goehl:

That sound like you like to raise a stink too.

Tracy Skaggs:

I love to raise a stink, I do. When I held this last rally here, which I do this typically in September for National Recovery Month, and the mayor was introduced to me. And I was acknowledged as the culprit. And where most people would have taken that wrong, I like that. I took that as a compliment. And all I could do is say, “Yes, sir. That is me. Remember my face because I’m only going to get louder from here.”

George Goehl:

Wow, Tracy, I will remember you. And I hope our listeners do too. I hope that you listening in that you all remember Tracy, and Tyla, and Dr. Cooke, and Kate. I hope you remember all of us, because we’re all going to join Tracy in getting louder from here. There’s a mythology at play that there’s been no voice for rural America small towns, that the only voices are conservative or racist.

And that’s how Donald Trump and the conservative right became the story of small towns. But I see a different story, one that I hope you do too. In Southern Indiana, I see a doctor, a mother, and a recovering addict doing their best to mobilize their community, eradicate their shame, and speak, and work with compassion to help their neighbors, and win change against the odds.

In New Jersey, I see a community that refuses to let itself be washed away, to do whatever it can to raise up survivors, fight climate change, and drown out the voices who tell them it’s impossible, and do all of it across, or despite partisanship.

In rural Iowa, I see an intergenerational, intersectional fight for the right to clean water, and a return to a stewardship of the earth. A David fighting Goliath of corporate greed and environmental contamination.

In North Carolina, I see friendships being forged in the face of centuries of racism, antiracist organizing happening at the corner of plantation, and corporation avenues. And a historical political candidate, a black woman quite literally from the wrong side of the tracks campaigning to co-govern with her community.

And in Michigan, I see what happens when we listen, truly listen, when we meet people where they are, when we honor each other’s lived experiences, and repair divides both political and personal. I see what happens when we see each other. Hey, I know this isn’t the whole story of small-town America. We’ve only scratched the surface.

But I started this podcast with an ask that you set aside your preconceptions of rural communities with a bunch of white people, to hear from people who are also waking. And now, I have another, reflect on who are you not seeing? What do you lose by not seeing them? What can you gain by listening better? What might we all gain?

If when listening to this, you’ve seen a person, or a community in a new light, maybe you’ve also seen the potential to build with people very different from you. Maybe in the past few months, you’re among the million seeing with fresh eyes, the hard truths about racism in our country, hard truths we all could have seen before if we really looked, if we saw each other, and refuse to give up on each other.

We’ve seen what happens when we give testimony, and when we bear witness. Good things happen when we see each other. Hey, I know it’s hard to, especially right now. But I believe that seeing each other can save individuals. It can liberate people. It can create space for people to come to new conclusions. And I know it can heal us, make us whole enough to move a community, or a country forward, and solve the problems at hand.

More than ever, we’re a nation of people reckoning with our past, and shaping what America will become next. For that next step to be more powerful, and long lasting, we got to bring along as many people as possible. Hey, I was an easy person to give up on. And I know some of these small towns were too. I hope these stories are a reminder of why we can’t. For more stories, and ways you can join in, head to peoplesaction.org/podcast. Thank you so much for listening.

To See Each Other is produced by People’s Action and The Mash-Up Americans. It is executive produced by Amy S. Choi and Rebecca Lehrer. Our senior producer is Sara Pellegrini. Our development producer is Melissa Low, and our production manager is Shelby Sandlin. To See Each Other is sound designed by Pedro Rafael Rosado, original music by The Tang Brothers.

Bonus Content

Dan Alexander's Story

Dan Alexander is a Bloomington, Ind.-based Hoosier Action leader and second generation worker at the Bedford GM plant and UAW member, who focuses on union efforts and small town factory workers.I’m originally from upstate New York, about six minutes from the Canadian border. My parents live in Bedford and now I live in Bloomington.

We moved to Bedford in 1987. Everybody was nice, but it was a little strange. The East Coast and Midwest mentalities were different. It’s very wholesome, very religious here. I come from a Catholic background, and when we moved here, we were in the minority. That was probably the biggest shock.

My mother was born on an Indian reservation. My grandmother, my mom—I’m Native American. When I moved here, I thought, well, we’re going to Indiana. Where are the Native Americans? The first time we came through, I saw a sign on the on the road that said “Monroe Res,” and I was like, oh, there’s a reservation. And my dad was like, no, that’s the reservoir. That’s a lake.

My dad was was a tool- and die-maker for General Motors. The plant where he worked closed, and one day he came home and said, I have to make a decision that you guys probably aren’t gonna like, but we have to move within the next two weeks. We were kids. My dad moved with my brother to Indiana, and we stayed on the reservation with my grandmother for seven months, I believe, until he could afford to come back and collect everything and bring us to Indiana.

Bedford is a very rural small town, but I went to a big high school. A lot of middle schools feed in there. We moved right in the middle of the Damon Bailey craze, Hoosier hysteria. I’d never even been to major school sporting events, and it was the biggest thing I’d ever seen. So many people watching a high school game just blew my mind.

My dad was a union member, and my brother and I are too. We were told from a young age that this is how someone who doesn’t have a college education can put four kids through college. That’s not so common these days. I work at an aluminum foundry. We do diecast work, transmission cases, stuff like that.

I was introduced to Hoosier Action when we were in the middle of a lengthy strike last year. A friend referred me to Kate, and I was impressed—they went into action quickly, they donated $1,500 worth of dry goods to the union, donated into our food pantry. It was an outpouring of kindness in a time when we weren’t sure if people were on board with what we were trying to do. That made an impact on me.

Some people seem to think that unions are out for themselves, and that’s not really the case. We were on strike for several reasons. Insurance was on the table, and we were trying to get permanent employment for temporary workers. They’re working alongside us, doing the same job, it’s only fair to make sure that they were getting brought up like we did. The whole point of a labor union is to make sure everybody’s getting a fair shake.

When the pandemic started, we went on a temporary layoff, and I wanted to do something positive with my time. You know, if you see somebody that needs a hand up, and you give it to them, you get a lot in return. It gives you a different perspective. So I saw an opportunity with Hoosier Action and decided I wanted to get involved. Right now we’re discussing helping our neighbors work out their unemployment. Find food. People are looking at getting evicted, so we’re working toward solutions for that.

It’s been hard to change minds. These old systems seem to not be working these days, and I think we need to consider what other people are doing—other towns, other counties, other states, other countries. You have to see what’s working and try to assimilate it. I mean, it’s going to take a lot of people getting on the same page, and it’s difficult. It’s a weird climate right now. Very divisive.

At Hoosier Action, we’re nonpartisan. We don’t want to exclude. We want everyone to know, hey, it’s not just for this political party or this demographic. Coronavirus doesn’t discriminate. It’ll take anyone. You might have a different opinion than I do, but when you lose a loved one, I feel bad. And I would hope you’d feel the same for me. That’s just empathy. Compassion.

Somebody once made a comment I like to remember: Who would you trust to take you to the hospital if you were injured or your life was threatened? Of course I would take someone who had a different political viewpoint. You’ve got to be able to trust your neighbor. Even if he doesn’t feel the same way you do, we’re a community.

I’m finding a lot of people are wanting to talk. They want somebody to listen to them. At any other time, people might be saying, I’m fine. Leave me alone. But people are worried. It’s uncertain times. People want to know that their needs are at least being listened to.

I try to be optimistic. I think a lot of people are just scared. You need to know that there are ways you can participate in trying to help solve the problem. Everybody can do something. You don’t have to solve everything overnight; obviously, nobody can. Just do your part and help out. And then if you get enough people together, that’s a huge impact. Everyone can get involved in some capacity, even if it’s the smallest thing. You know, checking on a friend making sure that they’re okay, if they’re cooped up, calling them, talking to them. Right now, we need to be making sure that people feel like they’re not forgotten.

All these Hoosiers–George included–testify to how when we see when we see each other, we strengthen our communities together. And we win.

Talking with Dr. William Scott

An extended conversation between George Goehl and Dr. William Scott, a Hoosier native and the doctor at the center of the HIV crisis in southern Indiana in 2015.What made you decide to become a doctor?

My mom was a nurse, so I’d been around hospitals. Then when I was 16, I sprained my ankle and was on crutches. I was still in pain when we went to a church service, and I felt this gnawing at my heart to make a commitment to do something with my life. After the service, I prayed with my pastor.

That night, my ankle swelled more. I noticed little dots all over my body, my gums started bleeding. My mom took me to a local urgent care center. They drew blood and discovered my platelet level was too low to count. We spent the next several days in a children’s hospital having tests, doctors coming in with residents and medical students. It felt odd that the very night I committed my life to helping people, I ended up in the hospital. I decided to pay attention and follow along with the doctors. It was fascinating—like a Sherlock Holmes mystery being solved.

We discovered I had idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura, which basically means my body was eating up all my platelets. I had to get a series of transfusions, in 1985, when people were afraid of contracting HIV that way.

Ryan White was in the news—the Indiana teenager who was diagnosed with AIDS in 1984 after getting HIV from a transfusion. His school banned him. There was so much fear and ignorance.

Yes. I was born the same year as Ryan, so I was really aware of that. I didn’t contract HIV, the blood supply was safe, but watching what Ryan went through made me want to fight fear and discrimination.

Why did you open your practice in Austin?

After my family medicine residency in 2004, I looked for a community where I could make the most difference. Austin hadn’t had a doctor since the last one retired in 1978. An entire generation grew up without local access to health care. It was the poorest community in the state; there was a high burden of disease, disability, and death.

Where did that burden originate?

It goes way back. After the Great Depression, people migrated out of Appalachia looking for opportunities. Morgan Foods, one of the largest food distributors in the world, needed workers in Austin. There was that factory town mentality you see in Appalachia with coal mining. People had temporary housing, dirt floors, no running water or electricity, but they got by because Morgan took care of them.

In the ‘70s, there was an economic downturn. Morgan wasn’t doing well, so Austin wasn’t doing well. In the ‘80s, unemployment was over 20%. You had people growing up in poverty, without basic needs being met, not feeling safe. There was toxic stress, and one way to cope with that is by taking opioids.

Tell me how that became a crisis.

The community started experiencing more injection opioid use. Typically, people crushed and snorted the medications. The formulation was changed to prevent that, so people figured out how to melt and inject it. This was an unintended consequence of efforts to decrease drug use. Clean syringes were illegal here, so people reused and shared them. They started spreading hepatitis C. We knew something devastating was happening—any community with hepatitis C will see HIV unless there’s intervention.

The first two HIV cases were diagnosed in December 2014. With contact tracing, another eight people were identified. Before this, we hadn’t seen a new HIV diagnosis for over ten years. In 2015, this town of 4,300 people had 200 HIV cases. It was the worst drug-related HIV outbreak in U.S. history, and the first rural outbreak.

We met with the state Department of Health, and I offered to open my office to anyone at risk or who’d contracted HIV. Governor Pence signed an emergency order exempting us from state law so we could run a syringe program. We brought in infectious disease doctors to help me learn about HIV care. We connected with behavioral health centers. We became a hub of care.

What did you learn about your patients as you built this care system?

They were injecting drugs. They were living with stress, trauma, and instability. The general consensus was that these people wouldn’t be willing to take care of themselves.

We met each person with respect and dignity, and provided an opportunity to feel safe and cared for, often for the first time in their lives. We found that people responded by taking care of their health—and the health of their community.

Needle sharing went from every person to 22% of users. It’s even better now. Over three quarters of our HIV patients suppressed their viral loads by taking medication. They’re willing to meet with me, and often, they allow me to help them get into recovery.

Your faith helped determine your profession. How does it influence you now?

I grew up in a fire-and-brimstone church. It was about making sure you’re right before God. Other people needed to get their lives right, too. If they lived righteous lifestyles, they wouldn’t experience harmful consequences.

When I went to Austin, I saw a whole community that had experienced structural violence. These people weren’t harmed because of personal choices they made, they were harmed by social sins. Society can sin against people by restricting how much access they have to life.

Now, there’s not just a relationship I need to have with God. There’s a responsibility I have to others.

Why did you get involved with Hoosier Action?

Bill Schafer reached out to me. He explained that Hoosier Action is working to get everyone access to healthcare, to keep people safe in the workplace. Part of what I’ve done as a doctor is to try to give a voice to people whose voices aren’t being heard. Hoosier Action does that on a larger scale throughout Indiana. Everyone needs a doctor. Investing in that isn’t Republican or Democratic, it’s just compassionate. It’s human.

Michelle Bloom's Story

Michelle Bloom is a Bloomington, Ind.-based leader at Hoosier Action who focuses on healthcare issues.I’m a born and bred Hoosier, from the Unionville area. Now I work for the Goodwill here in Bloomington, which I enjoy, because you interact with the community, you’re doing something that helps people. I miss it—I’m currently unemployed because of the Covid-19 situation. That’s been hard, as someone with depression. Even with medication, you still have moments where you get down, and one of the ways to prevent that is being active.

Hoosier Action was a happy accident for me. I do some writing on social media, on Facebook. It’s kind of my thing. I write about issues that are important to me, like health insurance, people living in poverty, homelessness. I was looking for an outlet, but I didn’t know how to connect with that kind of organization.

I wrote a post about an awful experience I had at a Bloomington hospital. I had a bad kidney stone, so I took an ambulance even though I don’t have health insurance. I waited forever. Then it was very hurried, very “Let’s get her out of here, she doesn’t have insurance.” They said, well, Medicaid sends you home with some prescriptions. They put me on fentanyl for the pain. I don’t own a vehicle and didn’t have money for a bus. I live on the east side, the hospital is on the west side, so I walked home under the influence of fentanyl. I was treated with such a lack of compassion. It was disheartening.

One of my friends happens to be a Hoosier Action member. She saw that post and tagged Eva, a Hoosier Action leader. Eva set up a meeting with me because she was interested in my story. We met for coffee, we had a good conversation, and it snowballed from there. Hoosier Action was a perfect fit for me, and I didn’t even know I was looking for them. I think a lot of people are looking for an outlet so their voice is heard. They just haven’t found it.

Right now, one of our big issues is that the state attorney general wants to repeal the Affordable Care Act. Thousands and thousands of Hoosiers would lose their health insurance. Before the pandemic, we were doing things more directly, going to the Statehouse, talking to legislators. Obviously now that’s not possible, so we do a lot online. We contacted the AG on his Facebook page, we shared videos talking about our personal health stories.

One of the things I’ve learned from working with Hoosier Action is how many issues there really are across the state. It’s not just poverty or the lack of health care. For example, in Martinsville, there’s a problem with pollution, people there have gotten sick. I didn’t realize how much Hoosiers are dealing with.

We want to be honest about what we’re dealing with in this state. That’s the only way anything’s going to change. We have to be straightforward about the things we’re facing, especially in this pandemic, and Hoosier Action encourages that kind of authenticity and honesty. If you’re toughing it out, or saying, “Oh, everything’s okay,” that’s not going to create change. Complete honesty about what you’re dealing with financially, emotionally, medically—that’s what generates change. Lawmakers won’t understand how important issues are if you don’t emphasize how they affect people. And if it’s just one person complaining about their situation, they won’t be heard. It takes coming together, organizing, putting pressure on legislators.

I love the local feel here. People know one another. It’s not overwhelming or noisy, but we’ve got access to culture and arts. If I could change something about Bloomington, though, it would be affordable housing. A lot of local people can’t afford the high rents that many of the students can. I wish the minimum wage was higher, so people could have a chance to thrive instead of just exist here. You know what’s sad? I make more in unemployment than I did when I was employed. To me, that says a lot about how much we need to raise the minimum wage in our state.

Before I got involved with Hoosier Action, I knew I wanted to change things, but I didn’t know what steps needed to be taken. They gave me those steps, and it’s not just writing letters or making phone calls, although we do that too—it’s meeting with legislators, being visible at the Statehouse, getting issues out there so the public knows what we’re fighting for.

And I’m an introvert. I was that kid who, if I had to give a speech in front of the class, I felt sick. This is the last thing I could’ve seen myself doing a year or two ago. Now, I’ve opened a meeting at Hoosier Action. I’ve been at news conferences. I’ve spoken on several Zoom meetings and told my story out loud. Hoosier Action has pushed me, in a good way. They’re like, Go, Michelle, go! They encourage you and build you up, so you feel comfortable doing things you’ve never done before. You go from feeling completely powerless, especially with depression, to feeling strong. You start to feel like a different person, like somebody who’s capable of more.